- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Paleontology»

- Prehistoric Life

Dinosaurs of the Year: 2014 Edition

During the first week of September, a 65-ton dinosaur from Argentina made the headlines and homepages of many American news sources. For laymen, this may have been a welcome distraction from ISIS, Ukraine, and other bad news at home and abroad. For dinosaur devotees and experts, this and a few other new genera described this year have the potential to alter and broaden our perspective of these animals as a whole.

Like a similar article I wrote at the end of last year, this list doesn't discuss every dinosaur discovery since January. Instead, it spotlights the most substantial, mold-breaking genera named and presented to the public in 2014, after years of rigorous excavation, preparation, and examination by their discoverers.

DINOSAURS OF THE YEAR

Anzu (North and South Dakota, 68-65.5 million BCE)

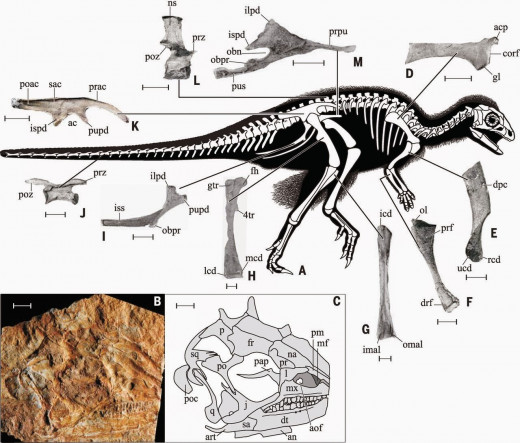

Since the 1920s, most oviraptorosaurs have been found in Chinese or Mongolian deposits. Paleontologists have also identified North American species of these strange, beaked theropods, though usually from fragmentary fossils. Between 1998 and 2013, however, fossil hunters collected four separate specimens of a new genus from the Hell Creek Formation. Like other Hell Creek dinosaurs (such as T. rex and Triceratops), Anzu was one of the largest, last, and most completely-known of its kind.

Though colorfully called "the Chicken from Hell" by various news sources, Anzu actually takes its name from a bird-like being from ancient Mesopotamian mythology. In life, adults would have stood well over six feet tall and weighed about a quarter of ton--much bigger than most oviraptorosaurs and second only to its Mongolian relative Gigantoraptor. Its dramatic head crest, stunted tail, larger hands, and broader feet also separated Anzu from most of its Asian kin. This latter feature may have helped the animal negotiate the coastlines and wetlands it inhabited, in contrast to the smaller feet of Mongolian desert-dwellers like Citipati.

Dreadnoughtus (Argentina, c. 75 million BCE)

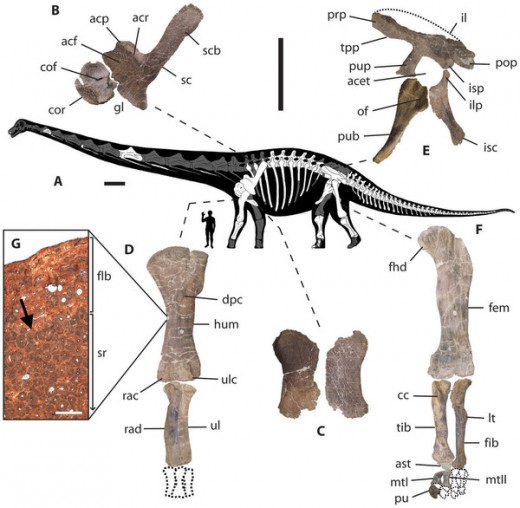

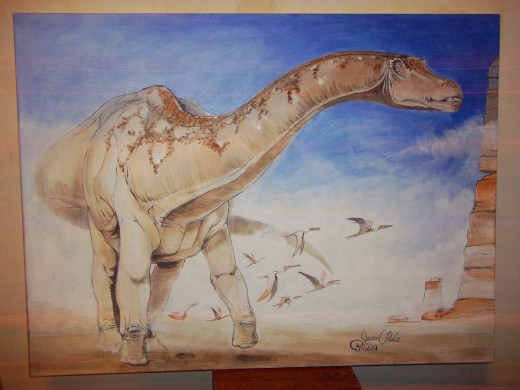

Dreadnoughtus may not be the largest known dinosaur. Among the candidates for this title, however, it is easily the most complete.

Between 2005 and 2009, paleontologists led by Kenneth Lacovara excavated two separate specimens of this titanosaur in the Patagonian province of Santa Cruz. These excavations yielded nearly half of the total skeleton, including most of the limbs, rib cage, and tail. Lacovara's team even found a Dreadnoughtus tooth and part of the muzzle--an amazing discovery in itself, since most sauropods are found without a trace of their comparatively tiny, fragile skulls. Dreadnoughtus' remains may prove crucial in helping paleontologists better understand titanosaurs as a whole. Though known from every continent but Antarctica, their fossils are generally much cruder, making the task of determining their core characteristics and evolutionary relationships a huge challenge.

Estimated to have reached about 85 feet long and 65 tons, Dreadnoughtus takes its name from the dreadnoughts--giant warships deployed during World War I. Beyond alluding to its size, Lacovara gave this herbivore the name for another reason: The term "dreadnought" literally means "fears nothing", and like modern African elephants and rhinos, he believes that adult Dreadnoughtus would have been extremely powerful, dangerous beasts with little to fear from the local large predators.

NOTE: Dreadnoughtus is not to be confused with another newly-discovered Argentine titanosaur covered by news sources this year. This still-unnamed dinosaur was found in Chubut (the province just north of Santa Cruz), lived roughly 20 million years earlier, and seems to have been even bigger.

Kulindadromeus (Russia, c. 169-144 million BCE)

For the past twenty years, paleontologists have unearthed and unveiled a multitude of feathered dinosaur fossils. Most of these finds concern advanced theropods, blurring the line between these hollow-boned, bipedal dinosaurs and birds (or, if you prefer, non-avian and avian theropods). Feathers or feather-like structures, however, are also known in a few ornithischians, a separate order of dinosaurs that includes the stegosaurs, hadrosaurs, and ceratopsians. Until now, the only confirmed examples were the ceratopsian Psittacosaurus and the heterodontosaur Tianyulong, both of which had tails lined with long, quill-like structures.

Kulindadromeus ("runner from the Kulinda fossil site") lacked the specialized beak, armor, or horns that characterize many ornithischians. But fossils of this diminutive Jurassic herbivore do preserve traces of filaments as well as scales. These filaments include not only lone fibers, but multiple structures branching from single stems, emulating the display and flight feathers of advanced theropods and modern birds. Since Kulindadromeus sits near the trunk of the ornithischian family tree, conceivably every member of this diverse group could have had ersatz or genuine feathers. Since feathers are so well-represented among theropods, these structures may even have been common to dinosaurs as a whole.

Qianzhousaurus (China, c. 70-65.5 million BCE)

Since 2009, paleontologists have described at least one new tyrannosaur genus each year. This year, they unveiled two: Nanuqsaurus ("polar bear lizard") from Alaska and Qianzhousaurus ("lizard from Qianzhou") from Jiangxi. Both grew to be around twenty feet long and lived about 70 million years ago. Yet while Nanuqsaurus' skull seems to have conformed to the thick-toothed, deep-skulled profile of T. rex and its close relatives, Qianzhousaurus had thinner, more numerous teeth and a set of longer (and probably weaker) jaws that earned it the nickname "Pinocchio Rex". This dinosaur also had a more pronounced set of horn-like structures lining its snout than other late tyrannosaurs.

The description of this strange predator supports the idea that smaller, slender-snouted tyrannosaurs coexisted with bigger, deeper-jawed genera at the end of the Cretaceous. Along with Alioramus--a Mongolian contemporary that also had beaky jaws and prominent horns--Qianzhousaurus may have hunted oviraptorosaurs and small ceratopsians. This strategy would have prevented it from directly competing with the much larger and more robust Tarbosaurus, just as modern cheetahs avoid confrontations with lions. It also may have spared these predators injuries from more dangerous dinosaurs like titanosaurs.

What was the most important dinosaur described in 2014?

HONORABLE MENTIONS

Amargastegos- Stegosaur from Early Cretaceous Argentina. The first stegosaur from South America.

Aquilops- Primitive, bipedal ceratopsian from Early Cretaceous Montana. The oldest member of the family known from North America.

Laquintasaura- Early ornithischian from Early Jurassic Venezuela. One of first two dinosaurs to be described from northern South America.

Leinkupal- One of the latest known diplodocids, from Early Cretaceous Argentina.

Nanuqsaurus- Comparatively small tyrannosaur from Late Cretaceous Alaska, measuring around 20 feet long and 1,000 lbs.

Tachiraptor- Small theropod from Early Jurassic Venezuela. Likely lived alongside and hunted Laquintasaura.

RENAMED DINOSAURS

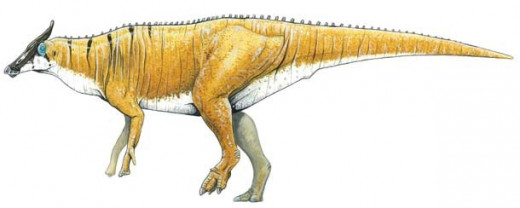

Augustynolophus- Latest Cretaceous crested hadrosaur from California, formerly known as "Saurolophus morrisi".

Eoplophysis- Mid-Jurassic stegosaur from England, formerly dubbed "Dacentrurus vetustus".

Gongpoquansaurus- Early Cretaceous iguanodont from China, formerly called "Probactrosaurus mazongshanensis."

Natronasaurus- Late Jurassic stegosaur from Wyoming, formerly regarded as "Stegosaurus longispinus".

SOURCES

Scientific Publications

Lacovara, Kenneth, Jason Poole et al. "A Gigantic, Exceptionally Complete Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur from Southern Patagonia, Argentina." Scientific Reports, September 2014.

Lamanna, Matthew C. et al. "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America." PlosOne, 19 March 2014.

Ulansky, R. E. "Evolution of the Stegosaurs." Dinosauria, p.1-35, 2014.

News Sources

"Aquilops americanus: Small Cat-Sized Dinosaur Discovered in Montana." sci-news.com, 11 Dec 2014.

"Changyuraptor yangi: New Feathered Dinosaur Discovered in China." sci-news.com, 16 Jul 2014.

Hone, Dave. "Siberian dinosaur spreads feathers around the dinosaur tree." The Guardian, 24 Jul 2014.

"Kulindadromeus zabaikalicus: Feathered Herbivorous Dinosaur Discovered." sci-news.com, 25 Jul 2014.

"Laquintasaura venezuelae: New Herbivorous Dinosaur Discovered in Venezuela." sci-news.com, 6 Aug 2014.

"Leinkupal laticauda: New Sauropod Dinosaur Discovered in Argentina." sci-news.com, 18 May 2014.

Morgan, James. "'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered." BBC News, 16 May 2014.

"Nanuqsaurus hoglundi: New Tyrannosaur Discovered in Alaska." sci-news.com, 13 Mar 2014.

"Qianzhousaurus sinensis: Long-Snouted Tyrannosaur Discovered in China." sci-news.com, 9 May 2014.

"Rukwatitan bisepultus: New Titanosaur Discovered in Tanzania." sci-news.com, 9 Sep 2014.

Schmemann, Serge. "A 65-Ton Dinosaur as a Distraction From NATO, Ukraine, and ISIS." The New York Times, 5 Sep 2014.

Switek, Brian. "Alioramus altai: A New, Multi-Horned Tyrant." Smithsonian News, 6 October 2009. (for more on Alioramus and Qianzhousaurus' place among tyrannosaurs)

Switek, Brian. "'Pearl' the Mystery Dinosaur." National Geographic News, 27 Nov 2013.

Other

ed. Eberth, David A. and David C. Evans. Hadrosaurs; Indiana University Press, Indianapolis and Bloomington, IN, 2014.

http://www.trieboldpaleontology.com (homepage of Triebold Paleontology, Inc., manufacturer of skeletal casts of Anzu and other paleontology-related products)

Paul, Gregory S. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs; Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2010. (for comparisons of Anzu with other oviraptorosaurs)